SAILING TO WINDWARD

These two sketches [ RIGS and RIGGING by Richard Henderson -page 187] outline idealized slots with proper trim and twist for light and medium winds for beating to windward.

The best way to check your sail trim is from another boat off of one of your stern quarters or even standing on shore [It is difficult to evaluate your sail trim when you are on the boat to being evaluated.] An even better approach is to capture the sail trim state with a camera.

Once you have captured the details of your windward sail trim, the big question is how you are going to use that information.

A. Blame your poor windward performance on the design of your craft. [ if the boat designer had wanted your boat to perform better, he would have added the necessary controls when the boat was made.]

OR

B. Work out a plan to add each control that is lacking over a period of time that is compatible with your financial and time resources.

What controls are necessary to achieve IDEAL SAIL TRIM.

THE ABILITY TO CONTROL THE FOLLOWING FUNCTIONS IS ESSENTIAL TO ACHIEVE IDEAL SAIL TRIM

#1 mainsail leech tension

#2 jib sail leech tension

#3 mainsail foot tension

#4 move jib sheet fairlead to inboard position

#5 move jib sheet fairlead to outboard position

#6 move genoa sheet fairlead to inboard position

#7 move genoa sheet fairlead to outboard position

#8 move mainsail sheet anchor to above centerline [to windward]

#9 move mainsail sheet anchor to below centerline [to leeward]

Ideal sail shape and trim for close-hauled sailing depends, of course, on the weather conditions, especially on the strength of the wind. On a beat the camber and twist of a boomless headsail is easier to control, because the sheet tension is then pulling the clew away from the tack and spreading the two corners apart. This greater controllability of the headsail shape means that the jib's leech can be made to conform better with the mainsail's vertical curve, and the slot can be optimized from head to foot.

Notice that in both sketches the slots are fairly uniform from head to foot, but the sails have been flattened with less curvature vertically as well as horizontally in the medium breeze. This results in more forward thrust, better ability to point, and less heeling. The shape is achieved by tensionning the luffs and tightening the sheets while moving their leads farther to leeward. The mainsheet lead is moved with the traveller, and the jib's lead is transferred to a rail track. As the wind increases, the jib's lead is moved further aft to increase the upper leech and widen the slot to reduce heeling.

In light winds, the sails are given more vertical curvature and camber to increase their power. The mainboom is on the boat's centerline, but the sheet has been moved slightly to windward of center so that it can be eased to allow some sail twist without having the boom end move to leeward, thus causing the main to choke the slot. The lower battens can hook to windward slightly, but the upper battens should not. The luff tension is slack to increase camber and move it further aft. Draft in the lower mainsail is controlled with outhaul tension. The foot should be slack in light airs and tensioned in heavier winds. The jib's leech follows the mainsail's curve and a fairly uniform slot is achieved by moving the jib lead inboard, easing the sheet, and pushing the lead a bit farther forward to prevent excessive leech curvature and sail twist. The jib's stay as well as it's luff are slacked to increase draft and move the maximum camber aft.

All of these adjustments create powerful sails for light airs, but it should be said that in a real drifting match, where the breeze is almost calm, the sails should be made much flatter to maximize projected area, minimize stalling and limit slatting in motorboat swells.

SAILING OFF THE WIND

When running before the wind, sails provide power through drag, and you must guard against one sail blanketing another. Blanketing occurs when the forward sail comes into the wind shadow of the after sail and is starved of non-turbulent air. This situation is caused by sailing by the lee, and the obvious solution is to head up a bit to give the forward sail clean air or, when a spinnaker is not carried , jibe over one of the sails and sail wing-and-wing.

must guard against one sail blanketing another. Blanketing occurs when the forward sail comes into the wind shadow of the after sail and is starved of non-turbulent air. This situation is caused by sailing by the lee, and the obvious solution is to head up a bit to give the forward sail clean air or, when a spinnaker is not carried , jibe over one of the sails and sail wing-and-wing.

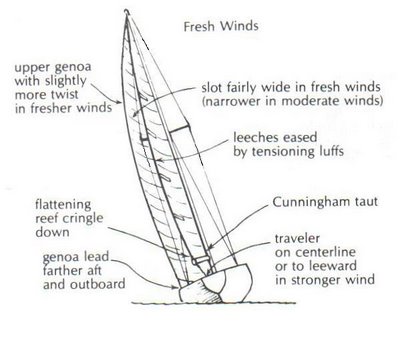

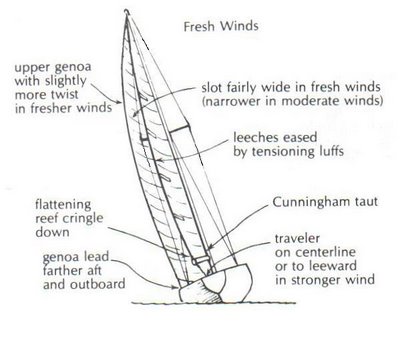

These two sketches [ RIGS and RIGGING by Richard Henderson -page 187] outline idealized slots with proper trim and twist for light and medium winds for beating to windward.

The best way to check your sail trim is from another boat off of one of your stern quarters or even standing on shore [It is difficult to evaluate your sail trim when you are on the boat to being evaluated.] An even better approach is to capture the sail trim state with a camera.

Once you have captured the details of your windward sail trim, the big question is how you are going to use that information.

A. Blame your poor windward performance on the design of your craft. [ if the boat designer had wanted your boat to perform better, he would have added the necessary controls when the boat was made.]

OR

B. Work out a plan to add each control that is lacking over a period of time that is compatible with your financial and time resources.

What controls are necessary to achieve IDEAL SAIL TRIM.

THE ABILITY TO CONTROL THE FOLLOWING FUNCTIONS IS ESSENTIAL TO ACHIEVE IDEAL SAIL TRIM

#1 mainsail leech tension

#2 jib sail leech tension

#3 mainsail foot tension

#4 move jib sheet fairlead to inboard position

#5 move jib sheet fairlead to outboard position

#6 move genoa sheet fairlead to inboard position

#7 move genoa sheet fairlead to outboard position

#8 move mainsail sheet anchor to above centerline [to windward]

#9 move mainsail sheet anchor to below centerline [to leeward]

Ideal sail shape and trim for close-hauled sailing depends, of course, on the weather conditions, especially on the strength of the wind. On a beat the camber and twist of a boomless headsail is easier to control, because the sheet tension is then pulling the clew away from the tack and spreading the two corners apart. This greater controllability of the headsail shape means that the jib's leech can be made to conform better with the mainsail's vertical curve, and the slot can be optimized from head to foot.

Notice that in both sketches the slots are fairly uniform from head to foot, but the sails have been flattened with less curvature vertically as well as horizontally in the medium breeze. This results in more forward thrust, better ability to point, and less heeling. The shape is achieved by tensionning the luffs and tightening the sheets while moving their leads farther to leeward. The mainsheet lead is moved with the traveller, and the jib's lead is transferred to a rail track. As the wind increases, the jib's lead is moved further aft to increase the upper leech and widen the slot to reduce heeling.

In light winds, the sails are given more vertical curvature and camber to increase their power. The mainboom is on the boat's centerline, but the sheet has been moved slightly to windward of center so that it can be eased to allow some sail twist without having the boom end move to leeward, thus causing the main to choke the slot. The lower battens can hook to windward slightly, but the upper battens should not. The luff tension is slack to increase camber and move it further aft. Draft in the lower mainsail is controlled with outhaul tension. The foot should be slack in light airs and tensioned in heavier winds. The jib's leech follows the mainsail's curve and a fairly uniform slot is achieved by moving the jib lead inboard, easing the sheet, and pushing the lead a bit farther forward to prevent excessive leech curvature and sail twist. The jib's stay as well as it's luff are slacked to increase draft and move the maximum camber aft.

All of these adjustments create powerful sails for light airs, but it should be said that in a real drifting match, where the breeze is almost calm, the sails should be made much flatter to maximize projected area, minimize stalling and limit slatting in motorboat swells.

SAILING OFF THE WIND

When running before the wind, sails provide power through drag, and you

must guard against one sail blanketing another. Blanketing occurs when the forward sail comes into the wind shadow of the after sail and is starved of non-turbulent air. This situation is caused by sailing by the lee, and the obvious solution is to head up a bit to give the forward sail clean air or, when a spinnaker is not carried , jibe over one of the sails and sail wing-and-wing.

must guard against one sail blanketing another. Blanketing occurs when the forward sail comes into the wind shadow of the after sail and is starved of non-turbulent air. This situation is caused by sailing by the lee, and the obvious solution is to head up a bit to give the forward sail clean air or, when a spinnaker is not carried , jibe over one of the sails and sail wing-and-wing.Of course, the smaller the offending sail and the farther it is from its victim, the less the blanketing.

There are times when a headsail can be carried successfully in the lee of the mainsail, if it is used in conjunction with a poled-out jib. The sails can be arranged to minimize blanketing by encouraging the air flow from leech to luff on the windward sail to spill into the wind-starved leeward sail. We carry a drifter-reacher opposite a poled out genoa on downwind legs when racing in non-spinnaker events, and the combination is astonishingly effective. In fact, my crew and I are often amazed that on certain occasions we can keep up with boats carrying spinnakers. This seems to indicate that not only twin jibs can be effective but also that spinnakers are not as beneficial as many sailors think.

So, the split jib of the KD seems like a pretty good solution to sailing downwind.